This piece is an updated version of a blog post I wrote here almost five years ago, when I still was an undergrad. That post is lost to oblivion, but this updated version happily made it to the preface of my PhD Thesis.

As many other biologists before me, yours truly hasn’t been the first (nor will be the last) to try and explain to himself what ‘life’ is (or what is it about), and would struggle to find a way to describe it in simple terms. In retrospect, the closest I have come to this is a simple list of three tightly interrelated concepts: diverse, responsive, and self-perpetuating. ‘Diverse’ because, despite the common building blocks that are biomolecules and cells, we observe a huge diversity of extant life forms: microscopic bacteria and unicellular eukaryotes, photosynthetic plants and algae transforming the energy of the Sun and making this planet hospitable, animals of all kinds predating on other organisms and among themselves, all of them occupying all niches and places one can think of as inhabitable (and even those ones one wouldn’t). Living organisms are responsive as dynamic systems capable of perceiving changes in an interacting environment and accordingly reacting at multiple levels (from physiological to behavioural). Along the same lines, species are not static because they are susceptible to changes and alterations that may confer upon them greater fitness over successive generations in time. This occurs as living forms self-perpetuate through reproduction, either at the unicellular or multicellular levels, either asexually or sexually. All these traits are linked to each other by another pivotal concept, the genetic program, in an interplay with consequences at the evolutionary time scale –that is, natural selection.

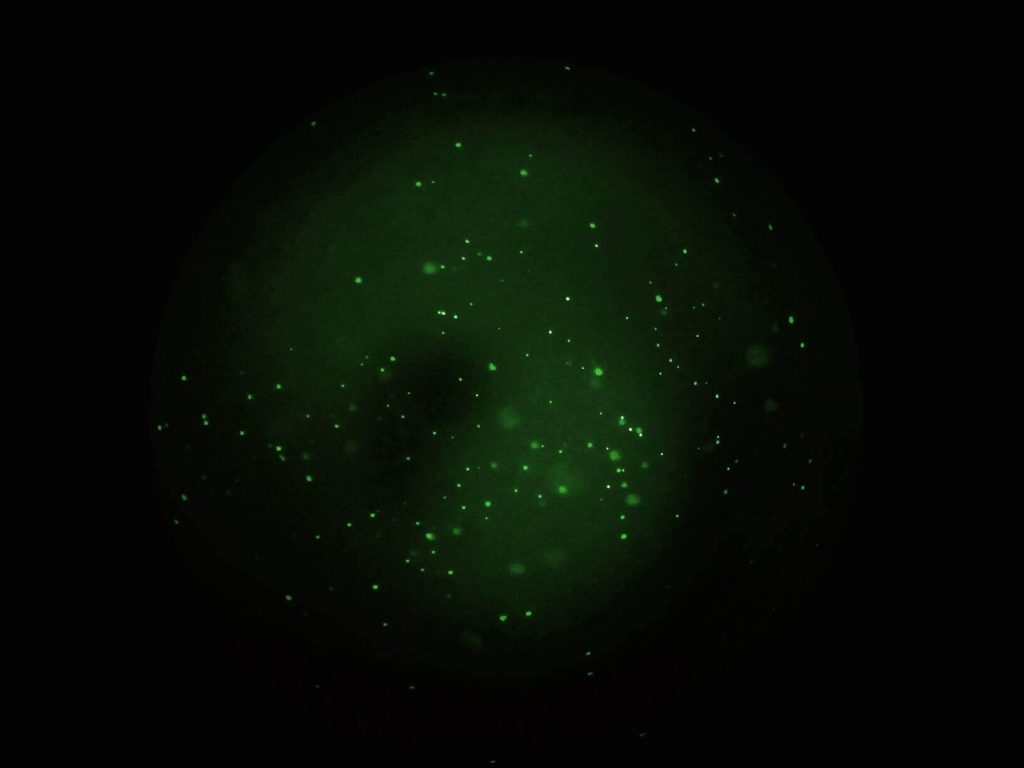

It is nothing but mesmerizing that the grandiose scenario that is life on Earth can be reduced to a minimal unit of function, the cell. Because all known life descends from a single ancestral cell, all life originates from a single-celled state, and a notable variety in all life is explained by differences in the arrangement and types of cells; all of it underpinned by the ever-running mechanism of cell reproduction, in turn regulated by a genome at the mercy of evolution’s whims.

Let us imagine, for a moment, a gene within a cell. That is, a sequence of DNA; a molecule formed by nucleotides, that is, smaller components. This gene’s product might be linked to a certain feature. This feature might be some sort of chemical activity within the cell, it might be the ability to respond to a cue, it might even be the ability to give rise to a cell lineage, responsible for giving rise to an essential component within a multicellular body plan.

Let us think, for a moment, about the many generations and processes of speciation during so many millions (I say again, ‘millions’) of years so that, just by chance and only chance, some changes in this molecule occurred, that some -but not all- of the changes were translated into a certain other feature, at first unnoticed, first in one organism, then transmitted to some, then to many, to the point of being present in all and thus becoming subjected to selection; that in turn this sequence gathered more changes, that some -but not all- provided a larger fitness, and were thus transmitted first to some, then to many, to the point that it became a normal feature in the species. Only to start over again. Let us think, for a moment, about this same process, only for all the features, all those details at the structural, metabolic, morphological and behavioral levels, that make a species what it is.

Hundreds, thousands, hundreds of thousands, perhaps millions of changes in the tiniest molecules, inappreciable molecules, for millions of years. And yet, as small as they are, they are so important. They determine so many things. They made you to be here, alive, sitting and about to read -and hopefully enjoy- my thesis, for example. And not only us as a species. Let us think, for a moment, of all those changes but for all the species, all the known and unknown species. All the organisms that were born, that were no more, that may have thrived, that may have not.

As many other biologists before me, yours truly is one who is fascinated when drifting away in this sea of thoughts, because when one stops and thinks of all the ‘genes within a cell’, in all the cells, in all of Earth’s history, it is inevitable to end up admiring the complexity and might of life, no matter the definition. To attempt and abstract the immensity of evolution of life on Earth down the level of cells, genes, and molecules, is a precious exercise to a researcher. An exercise that makes you feel very, very small.

But, at the same time, happy and proud to be part of something so big.